Cézanne and the Steam Railway (5)

: From Machinaiserie to Machinisme

Tomoki Akimaru (Art Historian)

Below is an abstract of my doctoral dissertation.

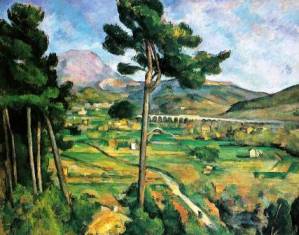

Fig. 1 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Bellevue 1882–1885 |

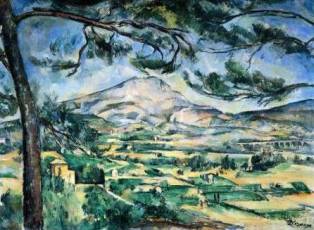

Fig. 2 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire and Large Pine c. 1887 |

|

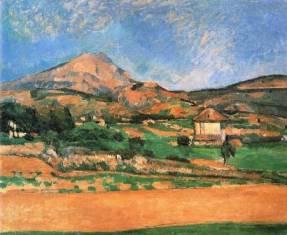

Fig. 3 Paul Cézanne The Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from the Chemin de Valcros 1878-1879 |

Fig. 4 A photograph of the scene in Fig. 3, photographed by the author on August 24, 2006. |

Interestingly, in his letter to Émile Zola dated April 14, 1878, only half a year after the opening of the Aix-Marseille line, Cézanne praised the Mont Sainte-Victoire, which he viewed from a speeding train that passed through the railway bridge at Arc valley, as a “beau motif (beautiful motif)” (1), and, subsequently, in about that same year, he began the series wherein he topicalized this mountain (Fig. 2-Fig. 4).

From these facts, we can assume that Cézanne initially drew the appearance of the steam railway and then gradually tried to “realize” on canvas the transformation of the visual perception induced by the steam railway as a “sensation.” (Fig. 5, Fig. 6)

Fig. 5 The Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from the train

while passing through the railway bridge at the Arc valley

(filmed by the author on August 26, 2006)

Fig. 6 The Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from the train

while passing through the railway bridge at the Arc valley

(filmed by the author on August 26, 2006)

Consider, then, the internalization of the influence of “Japan” on Western modern art, defined as the process from “Japonaiserie” to “Japonisme.”

In other words, while Japonaiserie is to simply draw, as a result of being influenced by the subject, goods made in Japan, such as the Uchiwa, Sensu, and Uchikake (Fig. 7), Japonisme is to express the influence of the form, such as the Japanese concept of space—for example, to express the influence through a painting in which the image exceeds the border (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7 Claude Monet La Japonaise 1876 |

Fig. 8 Claude Monet Water Lilies, Water Study 1914–1918 |

If the deeper internalization of influence required more time—that is, if the interpreting is later than the seeing—then the internalization of the influence of the “machine” in Western modern art is the transition from “Machinaiserie” to “Machinisme.”

In the case of railway paintings, it is understood that while Machinaiserie is to simply draw, as a result of the influence of the subject, the appearance of the railway system, which includes the railway station, telegraph pole and electric wires, railway cutting, railway signal, railroad, railway bridge, and steam locomotive, Machinisme is to express the influence of the form, that is, to depict the visual features internalized while riding a moving train on a painting by deforming objects, repeating transverse strokes, emphasizing horizontal ridgelines, and roughly depicting images of near objects.

Fig. 9 Claude Monet The Saint-Lazare Station, Arrival of a Train 1877 |

Fig. 10 Edgar Degas Landscape 1892 |

Among the impressionist painters who were associated with Cézanne, we can find typical Machinaiserie paintings by Claude Monet (1840–1926) and typical Machinisme paintings by Edgar Degas (1834–1917).

For instance, when Monet tackled the Saint-Lazare Station series in 1877 (Fig. 9), he said, “I’ve got it! The Saint-Lazare Station! I’ll show it just as the trains are starting, with smoke from the engines so thick you can hardly see a thing. It’s a fascinating sight, a regular dream world” (2).

On the other hand, in 1892, when Degas painted the landscape series influenced by the passing sceneries viewed from a running railcar (Fig. 10), he explained, “[The 21 landscape paintings are] the fruits of my journeys this summer. I stood at the doors of the coaches and I looked round vaguely. That gave me the idea to do the landscapes” (3).

Actually, Monet’s Saint-Lazare Station series pioneered the topicalization of the steam locomotive, which had not been drawn as an ugly monster. We can also presume that, because the deeper internalization of the steam railway’s in uence required more time, Degas’ painted representations of transformed vision induced by the passing sceneries seen from a moving train were created later than Monet’s topicalization of the appearance of the steam train.

Th us, we can logically conclude that the railway painter Paul Cézanne was the first impressionist painter who realized the shift from Machinaiserie to Machinisme.

(1) Paul Cézanne, Correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée par John Rewald, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1937; nouvelle édition révisée et augmentée, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1978, p. 165. (cf. Paul Cezanne, Letters, edited by John Rewald, translated from the French by Marguerite Kay, New York: Da Capo Press, 1995, p. 159.)

(2) Jean Renoir, Renoir, Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1962, p. 168. (Jean Renoir, Renoir, My Father, Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1962, pp. 174-175.)

(3) Edgar Degas, Lettres de Degas, recueillies et annotées par Marcel Guérin, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1931; nouvelle édition, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1945, pp. 277-278. (Edgar Germain Hilaire Degas, Letters, edited by Marcel Guerin, translated from the French by Marguerite Kay, Oxford: Bruno Cassirer, 1947, p. 252.)

This is a revised edition of “New Viewpoint on Art: Cézanne and Steam Railway (3)” published in Nihon Art Journal, May/June, 2012.